I’ve grown a fair share of hardy and tender plants from the genus Euphorbia, but truth be told, I’ve only scratched the surface. Comprising one of the largest plant families in the plant kingdom, Euphorbiaceae, commonly referred to as the spurge family, contains approximately 300 genera and about 7,500 species.

The best part of spurges is their infinite variety in plant form and function. Some are hardy workhorse perennials with more traditional forms, while others look more like Dr. Seuss plants. With a genus so diverse, there are species that will do well in nearly any part of North America.

Whether you’re new to Euphorbia or looking for more varieties to add to your garden, we have the information you need to be successful with this genus.

Great Varieties of Euphorbia

I’ll never forget my first visit to England thirty years ago. It was April, and the first garden I set foot in was the Royal Botanical Gardens at Kew. The large shrubby euphorbias every where were a sight to behold, since I was coming from the cold winter climate of the U.S. Mid-Atlantic region. I was sold that moment on these seemingly exotic plants. Since then, I’ve grown a fair share of hardy and tender plants from the genus Euphorbia, but truth be told, I’ve only scratched the surface. Comprising one of the largest plant families in the plant kingdom, Euphorbiaceae, commonly referred to as the spurge family, contains approximately 300 genera and about 7,500 species. It would take several lifetimes in many climatic zones to truly explore their full breadth. But throughout the United States and Canada there are spurges that will grow in your garden, either as hardy perennials or as potted plants summered outdoors and brought in for the cold months.

One thing all spurges have in common is their milky sap, which is very evident upon breaking or cutting a stem. This liquid latex, a lifeblood of Euphorbia, is a deterrent for animals, which would otherwise find these plants tasty. It also is a known skin irritant to some people, and therefore caution should be taken when working with these plants. But I would say that’s the only caveat of this useful genus. The best part of spurges is their infinite variety in plant form and function. Some are hardy workhorse perennials with more traditional forms, while others look more like Dr. Seuss plants. With a genus so diverse, there are species that will do well in nearly any part of North America.

Top euphorbia varieties for cooler climates

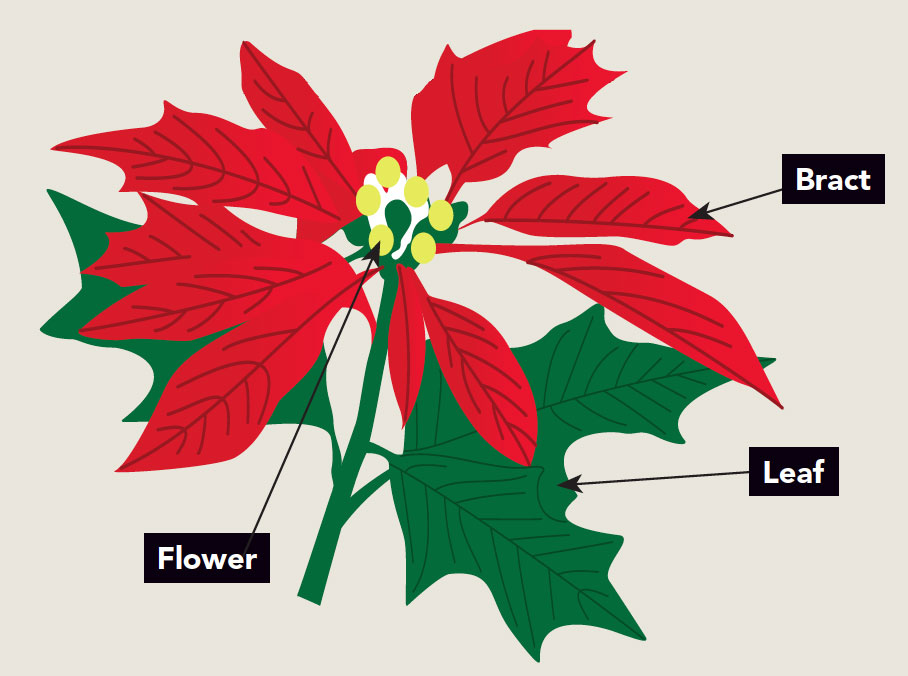

The first spurge I ever encountered, and one that I eventually grew in my first garden as a child, was cushion spurge (E. epithymoides, Zones 4–8). Its eye-catching chartreuse flowers held on a low 12- to 18-inch mound of foliage are a beacon in the awakening spring garden. It is one of the first herbaceous perennials of the spring season, its bracts positively glow, and it can be a companion to spring-flowering bulbs such as grape hyacinth and late-season tulips.

A real workhorse in the right situation is Robb’s spurge (E. robbiae, Zones 6–9). Because of its running tendencies, it is best used as a ground cover. It can take dry shade once established. Deep green leaves that form colonies sprout from lime green flowering stalks in midspring. In my experience, Robb’s spurge can be slow to establish; once settled, however, it can be pervasive, so keep it on its own or with other strong-willed perennials. Also, try to site it away from strong winter sun and desiccating winter winds in colder climates, which can burn the evergreen foliage and lead ultimately to losing a spring season of flowering.

The next three euphorbias have a similar form: their stems reach upward, then exponentially branch outward, forming an expanding mound 3 feet high and nearly as wide. Two are perennials, and the third is an annual that will reliably self-sow. Marsh spurge (E. palustris, Zones 5–10) is a large-scale perennial that is happiest when grown in moist or marshy ground, although it is not limited to such soils. An outlier in a genus that is known for being more suited to Mediterranean or desert climates, marsh spurge blooms in late spring with large heads of bright, acid yellow bracts. It is well suited for mingling with other moisture-loving plants, such as Siberian or Japanese iris (Iris spp. and cvs., Zones 4–9), and looks wonderful with late-blooming, large-headed flowering alliums (Allium spp. and cvs., Zones 3–9).

An underused U.S. native, flowering spurge (E. corollata, Zones 4–7) is only now getting some of its due, thanks to being featured in many Midwest prairie-inspired gardens, such as the Lurie Garden in Chicago, where Piet Oudolf has masterfully threaded it through the peak summer season’s riot of pinks, purples, and yellows. Flowering spurge emerges later than many perennials. Its stems with greenish-gray leaves grow straight upward, then diverge into a cloud-like effect of small white bracts. Think of it as a very tough baby’s breath (Gypsophila paniculata, Zones 3–9) that does not require staking! Now that it is becoming more widely known, nurseries are offering it for purchase. Young plants are slow to get established, but your patience will be rewarded.

Snow-on-the-mountain (E. marginata, annual) is an annual species that is native to the United States and Canada. It is very showy, with multitudinous stark white bracts that give it its frost-inspired common name. The seeds are hardy from Zone 5 southward, so you can expect this beauty to be reliably self-sowing. In fact, self-sown plants give the best results, as this annual resents transplanting. Scatter seeds where you want new plants to establish, and always allow some plants to go to seed each year to ensure a recurring show. Snow-on-the-mountain requires full sun and does well in average to lean soil.

‘Cherokee’ Martin’s spurge (E. × martinii ‘Cherokee’, Zones 6–8) is a cross between two different species, E. characias and E. amygdaloides. It has hybrid vigor and striking purple-red foliage. In spring, silvery-purple bracts cover the flowering stems. At less than 18 inches tall and wide, its size is compact, making it the perfect fit for the front of the garden. Perhaps best of all, it can take dry conditions once established.

Best euphorbias for warmer locales

It was twenty years after my first visit to England that I started experimenting with this second set of Euphorbia, which come from warmer regions of the world and, as such, are not as hardy as those in the first group. Their success in the garden relies on the top growth not getting zapped by intense winter cold. These are great plants for those living in warmer regions and even for those who live in cooler spots but like pushing the zonal limits or growing in containers.

‘Glacier Blue’ Mediterranean spurge (E. characias ‘Glacier Blue’, Zones 7–9) has enhanced blue leaves compared to the green-blue of the species. Each leaf is irregularly margined with white, which contrasts brilliantly with the blue. I’ve known this 2-foot-tall-and-wide plant to survive in Boston in protected places. Good drainage in winter, though, is key. Spring brings elongated spikes (12 to 18 inches tall) of variegated bracts that echo the leaves below.

‘Galaxy Glow’ Mediterranean spurge (E. characias ‘Galaxy Glow’, Zones 7–9) is a recent selection brought into the gardening world by plantsman Pat McCracken. The bluish leaves are burnished with coppery red tones, which is beautiful all on its own. Greenish bracts appear later in the season and are flushed with rose-bronze especially as they age. This is not a small plant—it can get up to 2 feet tall and spread much wider (nearly 3 feet is common)—so plan accordingly.

Many spurges can form a shrublike plant 3 to 5 feet tall and wide, which is awesome—if you have the space. A more diminutive option can be found in ‘Tiny Tim’ Martin’s spurge (E. × martinii ‘Tiny Tim’, Zones 7–9). It forms a compact shrublike ball only a foot high and wide and blooms not only in spring but also throughout the growing season. Each bract has a red “eye” in its center, which draws lots of attention for such dainty blooms.

Caribbean copper plant (E. cotinifolia, Zones 9–10) has deep, wine-colored rounded leaves and forms a 6- to 8-foot-tall-and-wide shrub or small tree over time. The foliage is reminiscent of a smoke bush (Cotinus spp. and cvs., Zones 4–9), and just like the colored-leaved forms of smoke bush, this woody spurge can be used to break up monotonous green foliage schemes or used as a dark foil for any number of flowering plants. It can also be planted in the garden in colder climates and overwintered in a frost-free room (expect it to get just 4 to 6 feet tall in this case). Plants can be left to go dormant and will resprout the following summer once the heat arrives.

‘Ascot Rainbow’ Martin’s spurge (E. × martinii ‘Ascot Rainbow’, Zones 7–9) has risen to prominence in the past decade, and for good reason. Its green leaves are irregularly variegated with yellow, augmented with highlights of bronze-red in cooler weather. The 12- to 18-inch-tall flower spikes also contain variegated bracts. I find in the Mid-Atlantic region that its stems are often winter-killed and that it is not as hardy as the similar-looking E. characias and its cultivars. It is great to use as an annual in a container, where it will continue to produce new flowering stems all season and look handsome well into autumn. In containers, store it in an unheated garage, and then put it out in early spring after the frost-free date.

Most of the spurges mentioned so far are upright, but silver spurge (E. rigida, Zones 7–10) is a sprawling, 2-foot-tall-and-wide, stiff-stemmed plant with blue stems and equally blue sharply pointed leaves. It blooms with acid yellow bracts in early spring on stems produced the season before. It thrives in hot, baking places that do not get much water, making it a perfect xeriscaping candidate. Silver spurge even thrives in the rocky home landscapes of places such as California’s Coachella Valley.

Some spurges are only hardy in a relatively small part of the country yet are becoming more popular in other regions as container plants for the summer season. There are hundreds of species of succulent spurge, all of which have adapted to extremely arid climates, their stems being a form of water storage. Sticks-on-fire (E. tirucallii ‘Rosea’, Zones 9–10) is a true eye-catching succulent that doesn’t fit the norms of what people in temperate climates think plants should look like. Basically, sticks-on-fire is a leafless shrub reaching up to 4 to 6 feet tall and wide in a pot, or up to 25 feet tall if planted in the ground in warm climates, with stems of yellow-green highlighted with pink and orange tones depending on the temperature. The growth rises upward and outward, bifurcating as it grows taller. Think of it as a living coral for your dryland garden. Sticks-on-fire mixes well with other succulent plants from arid regions and does very well in dry containers. It can be used as a houseplant in the winter months in a bright and sunny window. Just remember to acclimatize it to the outdoor sun upon moving it outside for the season.

Euphorbia Care and Quirks

Euphorbias, commonly known as spurges, are very easy to grow. They all need at least six hours of full sun, but more is generally better. Plants that don’t get enough sun will not bloom well or will have lax growth. An exception is Robb’s spurge (E. robbiae), which needs some shade.

Life span of euphorbia

Most spurges persist only for several years. The evergreen types tend to get woody bases that eventually succumb in winter.

Fertility

Overly rich soils promote soft growth, which is more prone to flopping. To avoid unnecessary staking, keep fertility moderate.

Toxicity

Wear gloves to avoid skin contact with the white sap, especially if working in full sunshine, as exposure to bright light can exacerbate the reaction. Also, keep gloved fingers away from your eyes.

Insects

The early spring-flowering species and cultivars provide pollen for pollinators when there aren’t many other food options. In addition, they attract ladybugs and other beneficial insects.

Pests

The pesky toxic sap makes the plants quite resistant to predation from deer, rabbits, and voles.

Moisture

With the exception of marsh spurge (E. palustris), good drainage is essential for all spurges. They will not survive winter if the soil is wet at that time of year. Most spurges are drought tolerant and are good candidates for xeriscaping.

How to Propagate Euphorbia

Most of the evergreen types of euphorbias will self-sow when the correct conditions present themselves. New seedlings can be removed from the plant when young. The non-evergreen types can be divided like most perennials in early spring or in early autumn. Evergreen and woody species can easily be grown from cuttings using these steps too.

Step 1

In spring before the flower buds emerge, take tip cuttings off the plant. They should be at least 1 inch long.

Step 2

Remove several leaves from the bottom of each cutting.

Step 3

Wash off the milky sap from the cuttings in cold water. Allow the cuttings to dry for at least a day and up to a week.

Step 4

Dip the end of each cutting into rooting hormone.

Step 5

Stick the bottom end of each cutting into a pot filled with potting mix and water. The cuttings should root within two weeks.

Photos: Danielle Sherry

The Dos and Don’ts of Pruning Euphorbia

Euphorbia growth is either caulescent (having stems above ground all year) or acaulescent (having only seasonal stems above ground). A third group of spurges, less common, stays woody year-round. These designations ultimately influence how a spurge is pruned back. It is very important not to cut back the stems of caulescent types in autumn; if you do, they will not flower the next spring. The acaulescent types go dormant in autumn, so the whole of the plant can be cut back to the ground. All types can be deadheaded after flowering (photo above) if neatness is a factor.

Group 1: Caulescent

In early spring, prune only dead stems from winter. Plants in this group include:

- Euphorbia ‘Galaxy Glow’

- E. robbiae and cvs.

- E. rigida and cvs.

- E. characias and cvs.

- E. × martinii and cvs.

Group 2: Acaulescent

In late fall, cut back the entire plant to the crown. Plants in this group include:

- E. marginata and cvs.

- E. palustris and cvs.

- E. epithymoides and cvs.

- E. corollata and cvs.

Group 3: Woody year-round

Trim any season just to shape. Plants in this group include:

- E. cotinifolia

- E. tirucallii ‘Rosea’

Gary Keim is a horticulturist and designer based in Landsdowne, Pennsylvania.

This article first appeared in issue #191 of Fine Gardening under the title “Spurge: Great Plant, Bad Name.”

Sources